Study: Russian Twitter bots sent 45k Brexit tweets close to vote

To what extent — and how successfully — did Russian backed agents use social media to influence the UK’s Brexit vote? Yesterday Facebook admitted it had linked some Russian accounts to Brexit-related ad buys and/or the spread of political misinformation on its platform, though it hasn’t yet disclosed how many accounts were involved or how many rubles were spent.

Today the The Times reported on research conducted by a group of data scientists in the US and UK looking at how information was diffused on Twitter around the June 2016 EU referendum vote, and around the 2016 US presidential election.

TheTimes reports that the study tracked 156,252 Russian accounts which mentioned #Brexit, and also found Russian accounts posted almost 45,000 messages pertaining to the EU referendum in the 48 hours around the vote.

Although Tho Pham, one of the report authors, confirmed to us in an email that the majority of those Brexit tweets were posted on June 24, 2016, the day after the vote — when around 39,000 Brexit tweets were posted by Russian accounts, according to the analysis.

But in the run up to the referendum vote they also generally found that human Twitter users were more likely to spread pro-leave Russian bot content via retweets (vs pro-remain content) — amplifying its potential impact.

From the research paper:

During the Referendum day, there is a sign that bots attempted to spread more leave messages with positive sentiment as the number of leave tweets with positive sentiment increased dramatically on that day.

More specifically, for every 100 bots’ tweets that were retweeted, about 80-90 tweets were made by humans. Furthermore, before the Referendum day, among those humans’ retweets from bots, tweets by the Leave side accounted for about 50% of retweets while only nearly 20% of retweets had pro-remain content. In the other words, there is a sign that during pre-event period, humans tended to spread the leave messages that were originally generated by bots. Similar trend is observed for the US Election sample. Before the Election Day, about 80% of retweets were in favour of Trump while only 20% of retweets were supporting Clinton.

You do have to wonder whether Brexit wasn’t something of a dry run disinformation campaign for Russian bots ahead of the US election a few months later.

The research paper, entitled Social media, sentiment and public opinions: Evidence from #Brexit and #USElection, which is authored by three data scientists from Swansea University and the University of California, Berkeley, used Twitter’s API to obtain relevant datasets of tweets to analyze.

After screening, their dataset for the EU referendum contained about 28.6M tweets, while the sample for the US presidential election contained ~181.6M tweets.

The researchers say they identified a Twitter account as Russian-related if it had Russian as the profile language but the Brexit tweets were in English.

While they detected bot accounts (defined by them as Twitter users displaying ‘botlike’ behavior) using a method that includes scoring each account on a range of factors such as whether it tweeted at unusual hours; the volume of tweets including vs account age; and whether it was posting the same content per day.

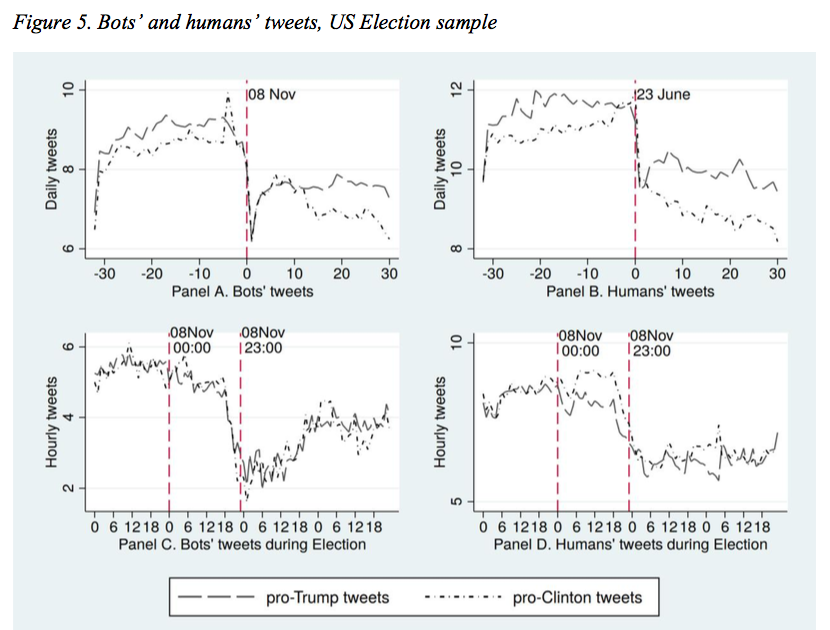

Around the US election, the researchers generally found a more sustained use of politically motivated bots vs around the EU referendum vote (when bot tweets peaked very close to the vote itself).

They write:

First, there is a clear difference in the volume of Russian-related tweets between Brexit sample and US Election sample. For the Referendum, the massive number of Russian-related tweets were only created few days before the voting day, reached its peak during the voting and result days then dropped immediately afterwards. In contrast, Russian-related tweets existed both before and after the Election Day. Second, during the running up to the Election, the number of bots’ Russian-related tweets dominated the ones created by humans while the difference is not significant during other times. Third, after the Election, bots’ Russian-related tweets dropped sharply before the new wave of tweets was created. These observations suggest that bots might be used for specific purposes during high-impact events.

In each data set, they found bots typically more often tweeting pro-Trump and pro-leave views vs pro-Clinton and pro-remain views, respectively.

They also say they found similarities in how quickly information was disseminated around each of the two events, and in how human Twitter users interacted with bots — with human users tending to retweet bots that expressed sentiments they also supported. The researchers say this supports the view of Twitter creating networked echo chambers of opinion as users fix on and amplify only opinions that align with their own, avoiding engaging with different views.

Combine that echo chamber effect with deliberate deployment of politically motivated bot accounts and the platform can be used to enhance social divisions, they suggest.

From the paper:

These results lend supports to the echo chambers view that Twitter creates networks for individuals sharing the similar political beliefs. As the results, they tend to interact with others from the same communities and thus their beliefs are reinforced. By contrast, information from outsiders is more likely to be ignored. This, coupled by the aggressive use of Twitter bots during the high-impact events, leads to the likelihood that bots are used to provide humans with the information that closely matches their political views. Consequently, ideological polarization in social media like Twitter is enhanced. More interestingly, we observe that the influence of pro-leave bots is stronger the influence of pro-remain bots. Similarly, pro-Trump bots are more influential than pro-Clinton bots. Thus, to some degree, the use of social bots might drive the outcomes of Brexit and the US Election.

In summary, social media could indeed affect public opinions in new ways. Specifically, social bots could spread and amplify misinformation thus influence what humans think about a given issue. Moreover, social media users are more likely to believe (or even embrace) fake news or unreliable information which is in line their opinions. At the same time, these users distance from reliable information sources reporting news that contradicts their beliefs. As a result, information polarization is increased, which makes reaching consensus on important public

issues more difficult.

Discussing the key implications of the research, they describe social media as “a communication platform between government and the citizenry”, and say it could act as a layer for government to gather public views to feed into policymaking.

However they also warn of the risks of “lies and manipulations” being dumped onto these platforms in a deliberate attempt to misinform the public and skew opinions and democratic outcomes — suggesting regulation to prevent abuse of bots may be necessary.

They conclude:

Recent political events (the Brexit Referendum and the US Presidential Election) have observed the use of social bots in spreading fake news and misinformation. This, coupled by the echo chambers nature of social media, might lead to the case that bots could shape public opinions in negative ways. If so, policy-makers should consider mechanisms to prevent abuse of bots in the future.

Commenting on the research in a statement, a Twitter spokesperson told us: “Twitter recognizes that the integrity of the election process itself is integral to the health of a democracy. As such, we will continue to support formal investigations by government authorities into election interference where required.”

Its general critique of external bot analysis conducted via data pulled from its API is that researchers are not privy to the full picture as the data stream does not provide visibility of its enforcement actions, nor on the settings for individual users which might be surfacing or suppressing certain content.

The company also notes that it has been adapting its automated systems to pick up suspicious patterns of behavior, and claims these systems now catch more than 3.2M suspicious accounts globally per week.

Since June 2017, it also claims it’s been able to detect an average of 130,000 accounts per day that are attempting to manipulate Trends — and says it’s taken steps to prevent that impact. (Though it’s not clear exactly what that enforcement action is.)

Since June it also says it’s suspended more than 117,000 malicious applications for abusing its API — and say the apps were collectively responsible for more than 1.5BN “low-quality tweets” this year.

It also says it has built systems to identify suspicious attempts to log in to Twitter, including signs that a login may be automated or scripted — techniques it claims now help it catch about 450,000 suspicious logins per day.

The Twitter spokesman noted a raft of other changes it says it’s been making to try to tackle negative forms of automation, including spam. Though he also flagged the point that not all bots are bad. Some can be distributing public safety information, for example.

Even so, there’s no doubt Twitter and social media giants in general remain in the political hotspot, with Twitter, Facebook and Google facing a barrage of awkward questions from US lawmakers as part of a congressional investigation probing manipulation of the 2016 US presidential election.

A UK parliamentary committee is also currently investigating the issue of fake news, and the MP leading that probe recently wrote to Facebook and Twitter to ask them to provide data about activity on their platforms around the Brexit vote.

And while it’s great that tech platforms finally appear to be waking up to the disinformation problem their technology has been enabling, in the case of these two major political events — Brexit and the 2016 US election — any action they have since taken to try to mitigate bot-fueled disinformation obviously comes too late.

While citizens in the US and the UK are left to live with the results of votes that appear to have been directly influenced by Russian agents using US tech tools.

Today, Ciaran Martin, the CEO of the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) — a branch of domestic security agency GCHQ — made public comments stating that Russian cyber operatives have attacked the UK’s media, telecommunications and energy sectors over the past year.

This follow public remarks by the UK prime minister Theresa May yesterday, who directly accused Russia’s Vladimir Putin of seeking to “weaponize information” and plant fake stories.

The NCSC is “actively engaging with international partners, industry and civil society” to tackle the threat from Russia, added Martin (via Reuters).

Asked for a view on whether governments should now be considering regulating bots if they are actively being used to drive social division, Paul Bernal, a lecturer in information technology at the University of East Anglia, suggested top down regulation may be inevitable.

“I’ve been thinking about that exact question. In the end, I think we may need to,” he told TechCrunch. “Twitter needs to find a way to label bots as bots — but that means they have to identify them first, and that’s not as easy as it seems.

“I’m wondering if you could have an ID on twitter that’s a bot some of the time and human some of the time. The troll farms get different people to operate an ID at different times — would those be covered? In the end, if Twitter doesn’t find a solution themselves, I suspect regulation will happen anyway.”

Featured Image: nevodka / iStock Editorial / Getty Images Plus

Published at Wed, 15 Nov 2017 17:42:58 +0000