In comparison to an anemic 2016 for venture-backed technology IPOs, 2017 was a much better year. Companies as diverse as Yext, Cloudera, Blue Apron, StitchFix, and SendGrid all went public last year, not to mention one of the most anticipated IPOs of the past few years, Snapchat. Looking forward to this year, there are a bunch of potential companies on the docket that could go public, and times couldn’t be better given the record highs of the S&P 500 and the Dow.

Now, I know what you are thinking: you just declared the IPO dead this year, you weekend clickbaiter. How can a robust market be the death of the IPO? Well, you clicked, so let’s get started.

There are growing dark clouds on the horizon for the future of IPOs. It looks likely that Spotify will run a direct listing, bypassing bank underwriting on the way to the public markets. Blockchain is increasingly drawing the attention of retail investors cynical of IPOs and their corruption. And funds like the SoftBank Vision Fund are increasingly raising private capital to protect companies from the ravages of vulture funds.

At issue is an increasing awareness that the current IPO system is corrupt beyond belief, an insiders game at the end of a company’s growth cycle that rewards those who know the right people while shortchanging retail investors in the process. That awareness is not going to recede, especially when alternative options are increasingly viable.

I caveat this prediction of the death of the IPO by noting that their supposed death has been predicted many times before. When Google decided to do a Dutch auction-style initial offering more than a decade ago, commentators predicted it could spell doom for banks looking to run investor roadshows. When the IPO pipeline dried up a few years ago, commentators were again saying that this was it.

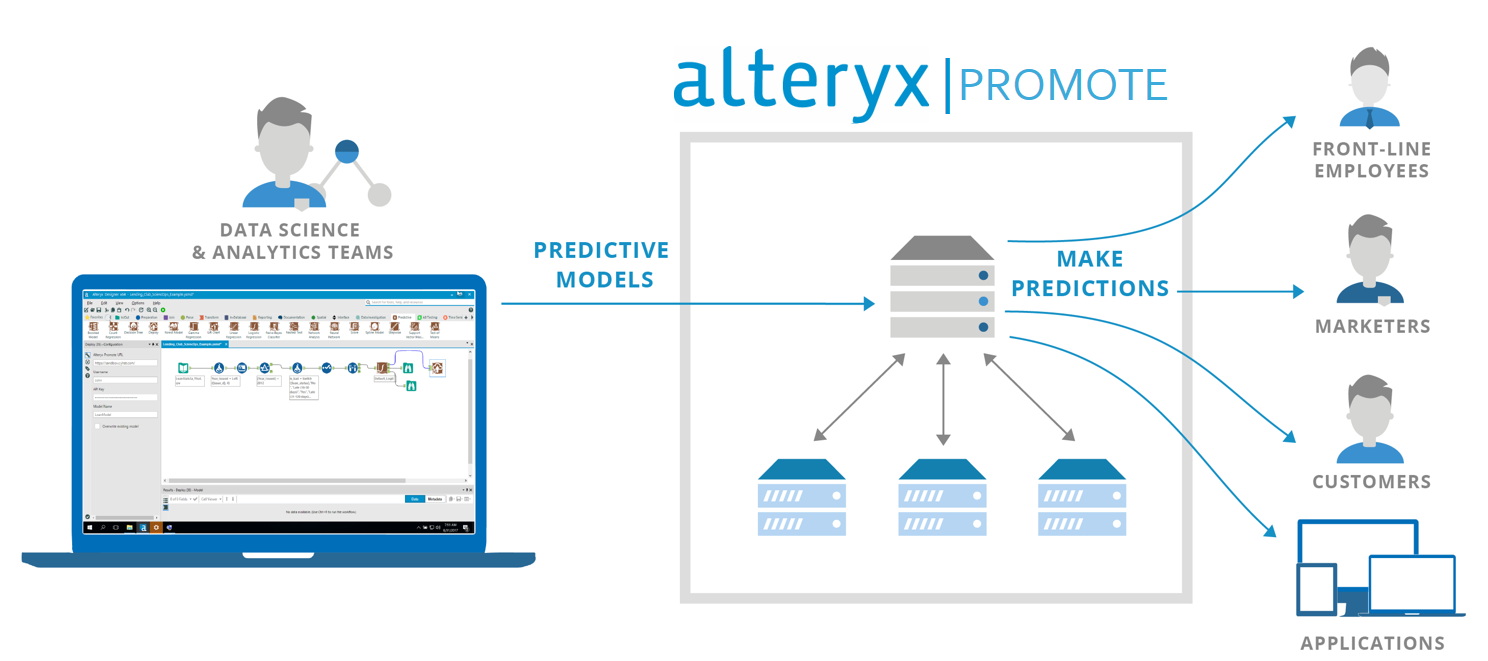

Obviously, companies are going to “go public,” in the sense that they will publicly trade a security of some kind. What’s changing though is that the old regime of big banks charging large fees to underwrite an IPO is crumbling and being replaced by a robust set of alternatives. Bankers are even starting to lose their jobs to automation — Goldman Sachs, for instance, has already developed software to handle the IPO process. One can’t help but see this as a bid to increase efficiency to compete.

For the IPO industry, direct listings are a disruptive disaster in the making.

I think few could have predicted that the life of the IPO would be bookended by the Dutch East India Company and the Useless Ethereum Token. Such is life. But make no mistake: the health of the IPO as it stands today has never been weaker. Without an immediate resuscitation, I don’t think it can make it.

Spotify

Spotify hit some pretty high highs and low lows this week. The company announced that it had grown to 70 million paying subscribers, while Nielsen data showed that Americans now get a majority of their music from streaming services. At the same time though, Stefan Blom, the company’s chief content officer, left the company. And recent news of a massive lawsuit filed by music labels against the company certainly adds some dark clouds around the future of the business.

But the big news this week was that Spotify has filed confidentially with the SEC to go public sometime in the coming weeks. And based on a steady state of rumors going back months, it looks like the company intends to continue with a direct listing.

Direct listings are relatively rare, although are hardly novel. Companies that direct list still file most of the same information to the SEC (albeit on different forms). They also need to list on an exchange that accepts them, such as NASDAQ or the NYSE, which recently proposed to the SEC a policy change to allow direct listings. A little more hand waves and magic (i.e. logistics), and then one day the company starts publicly trading.

In a direct listing, Spotify won’t issue new shares, and thus, it won’t raise any capital in the process. It won’t go on an investor roadshow, nor will it hire bankers to underwrite the offering to help stabilize the debut price. It also won’t lockup inside shareholders for months — all of whom will theoretically be able to trade on day one.

For the IPO industry, direct listings are a disruptive disaster in the making. Big banks like Goldman Sachs are going to miss out on their traditional underwriting fees (which can reach tens of millions of dollars), and institutional investors who are used to buying IPO shares before they go public — often at a massive discount — are similarly locked out of the process.

Spotify’s debut will be bumpy, considering that direct listings have much less of a cultivated playbook around them to ensure they are executed effectively. Liquidity may well be extremely tight on the first day of trading, which will cause large gyrations in the stock price. The traditional goal of bank underwriters is to limit volatility for a new issue, and a direct listing is about as far from that as possible.

Why wait for shares to become available at the end of the growth cycle when you can just buy the token today and ride a company’s success?

But, that doesn’t mean it will be as disastrous as some commentators are talking about. The rise of algorithmic trading means that computers increasingly make the decision to buy and sell in the public markets. So when Spotify comes to market along with its financial data, those algorithms will analyze the stats and stabilize the price as fast as they do for any other IPO debut. Spotify also has the advantage of a powerful consumer brand which should help prop up its stock price among human traders as well.

Now, maybe Spotify is a one-off just like Google’s Dutch auction was a one-off. But Spotify’s direct listing is much cheaper as well as more efficient and democratic. A strong performance by the company could see a slew of other companies go the direct listing route this year and into the future.

Initial Coin Offerings & SoftBank

If all goes well though, Spotify is still going to end up on a public stock exchange, likely the NYSE. There are other forces of democratization and privatization though that are working against the future of IPOs: ICOs on one hand, and late-stage private capital on the other, best exemplified by the $98 billion SoftBank Vision Fund.

ICOs have been all the rage these days, as TechCrunch headlines and discussions with Uber drivers, baristas, and hairstylists can attest to. The ICO market went from a dribble of capital at the start of 2017 to end up at over $3.7 billion in capital fundraised by the end of the year.

Few people are as excited about the potential for ICOs as founders. As I wrote last month, founders can use the ICO process to not just finance their companies without dilution, but also to increase user engagement, optimize governance, and potentially edit the signals they send to traditional VCs.

Now, ICOs are generally considered a replacement for venture capital, and not for the public markets. But that in my mind is more a question of scale than of any sort of specific factor about these processes. When companies are occasionally raising $250 million or more in a single ICO compared to a median IPO fundraise of slightly less than $100 million, it’s a real alternative.

At least in theory, once a company conducts its ICO, the tokens the company sells are free to trade, which means that the company has “gone public,” albeit in a different way. Although participating in an ICO still requires some serious technical skills today, its increasing democratization will continue as product UX for purchasing tokens improves.

Given the rush of ICOs among startups these days, it is perhaps an interesting thought experiment to project forward into the future what an IPO market looks like. Offering shares on a public market is really just adding another security to the company’s roster, given that the startup’s tokens would have already been freely traded, potentially for years. Why wait for shares to become available at the end of the growth cycle when you can just buy the token today and ride a company’s success?

What I see here is a bifurcation of the ownership of a company and who owns the growth of that company. In a traditional equity model, shares of a company are the only currency, and offer both governance and financial reward. But ICOs separate the two, allowing a retail investor to gain access to future business growth without buying governance.

There are many analysts who see that as a fundamental violation of the shareholder revolution and the theory of the firm. How can anyone invest in a company if they don’t even have the slightest control over that company’s destiny? But do shareholders — retail shareholders at least — really have any control in today’s public markets anyway?

ICO models may not apply to all companies of course. But as a competitive threat to IPOs, they don’t have to apply to everyone. Even reducing the number of companies heading to the public markets will make it harder for other companies to IPO as liquidity and attention wane.

ICOs are a route around the IPO that is more democratic than today’s system, but there are also forces of privatization working against IPOs as well. Perhaps nothing exemplifies this trend better than the rise of the SoftBank Vision Fund, the $98 billion behemoth that has been taking enormous bets in startups as diverse as Compass, Slack, and Mapbox. SoftBank’s CEO Masayoshi Son has said that he wants to construct even larger funds in the future, so expect their ambitions to continue.

For institutional investors, such funds are the “new IPO” — an opportunity to get into the late stages of growth in a company without waiting for its debut on a stock exchange. And while there is no actively traded market for these securities today, it is entirely reasonable to believe that companies could integrate an investment from a fund like SoftBank’s with a direct listing. Why go through a road show if you can just call two people and get the whole thing done instantly?

Like ICOs, this private late-stage capital is usually considered either a replacement for growth capital or just another stage of financing. But I think there is something to the notion that more companies will just elect to stay private, control their governance, and go on their merry way.

In short, IPOs are facing a fusillade of attacks. Direct listings cut out many of the middlemen and fees that the traditional IPO process has prioritized. And while direct listings disrupt the IPO directly, ICOs and privatization essentially make them moot. Companies today have a much wider repertoire of tools to finance growth, and going public is no longer the brass ring it once was.

The IPO is dead. Long live going public.

Featured Image: Mario Tama / Getty Images News/Getty Images

Published at Sat, 06 Jan 2018 19:35:17 +0000